Andy and I have traveled onward to Pretoria, South Africa because last night we saw Mating Birds by Lewis Nkosi— a prison-themed play at the State Theater. You’ll get the full report on that in a later post.

Here I am in part of the Old Fort section of the Constitution Hill prison in front of what looked like a little guard house.

My last post introduced our trip to Constitution Hill, but I didn’t have the energy last night to finish the story or to convey how incredibly moving our trip to the former prison was. In a room just off the Visitor’s Center of the museum, a short film provides an introduction to the prison. The opening of the film shows formerly incarcerated men and women returning to Constitution Hill to visit the place where they had endured years of deprivation, humiliation, and even torture. The film asserts that in coming back to the prison, these people are “reclaiming their dignity.” Just as the museum serves to remind all visitors of South Africa’s troubled past, the formerly incarcerated are living evidence that such struggles are neither forgotten nor distant from the present day.

South Africa is currently celebrating twenty years since the fall of Apartheid in 1994–often labeled as “twenty years of democracy” in a number of tee shirts and banners that we’ve seen since our arrival here. The legacies of colonialism, segregation, and brutal oppression remain apparent here, as they do in my own country, and the divides created by this history are nowhere more apparent (in any country) than inside prisons. During Apartheid and in the present, blacks were and are incarcerated at disproportionate rates to their white counterparts (as has long been and remains the case in my country), and at Constitution Hill one can see quite clearly that blacks filled a far greater part of the prison and that whites had significantly superior living conditions.

We saw the black men’s section of the prison first. Despite the fact that some of the prison’s buildings no longer stand, we saw room after cement room where men slept like sardines in a can. They had only blankets or thin pallets on which to sleep, and they were forced to sleep so close together that each man’s head was wedged between two sets of other people’s feet. An open toilet stands in the corner of each of these rooms, and the poorest and weakest men had to sleep nearest to the stench of the sewer. The museum has allowed the peeling paint, cold walls and floor to speak for themselves, adding little more than a few tasteful signs to help explain how the rooms were inhabited. Rough gray prison blankets with a few white stripes at each end have been made into skillfully constructed “blanket sculptures” to show where the bodies of the prisoners would have lain at night. These stand ins for actual people prove not only more artistic but also more moving than the tacky mannequins that dwell in so many museum tableaus. Constitution Hill prisoners actually made these sorts of blanket sculptures during their incarceration. They also engaged in paper maché and other forms of sculpture. The blanket sculptures on display at Constitution Hill’s museum today were made by two formerly incarcerated men who returned to contribute to this part of the museum.

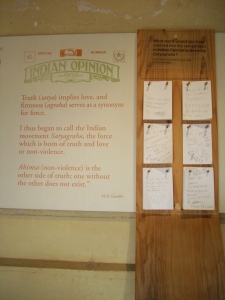

Such evidence of participation by former prisoners in the curation of the museum appears throughout the many exhibits on Constitution Hill, as do opportunities for visitors to respond to what they are seeing. Message boards appear throughout the exhibits, posing specific questions to visitors and encouraging them to share their thoughts about things like whether the people described in the exhibit were unjustly imprisoned or what Ghandi’s most significant legacy to South Africa might be. The notion that visitors’ active participation in the museum, indeed in South Africa’s ongoing history, falls in line with the objectives of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s efforts to capture the experiences of everyday people alongside the largest events in South African civil unrest. Most of the visitors’ comments I read throughout Constitution Hill expressed gratitude for the museum itself and for the opportunity to learn about and share in the history recorded there.

Such evidence of participation by former prisoners in the curation of the museum appears throughout the many exhibits on Constitution Hill, as do opportunities for visitors to respond to what they are seeing. Message boards appear throughout the exhibits, posing specific questions to visitors and encouraging them to share their thoughts about things like whether the people described in the exhibit were unjustly imprisoned or what Ghandi’s most significant legacy to South Africa might be. The notion that visitors’ active participation in the museum, indeed in South Africa’s ongoing history, falls in line with the objectives of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s efforts to capture the experiences of everyday people alongside the largest events in South African civil unrest. Most of the visitors’ comments I read throughout Constitution Hill expressed gratitude for the museum itself and for the opportunity to learn about and share in the history recorded there.

Constitution Hill had quite a few isolation cells throughout its many buildings. In the white male section of the prison, the isolation cells had a small desk bolted to the wall and wooden floors. Nowhere in the prison did we see a bed. It seems that everyone slept on pallets or the gray wool blankets on the floor. The white prisoners’ isolation cells were stark and intimidating, even though they were about twice as large as the isolation cells for black men and women. I couldn’t help wondering what those slight differences would mean to a captive. How much comfort and human dignity does a wooden floor lend as opposed to a cold concrete one? What fragment of one’s sanity and emotional stability might be better held in place by a few more feet of space in which to move?

I held myself together until we saw the black men’s isolation cells. As I have felt in most of the prisons I’ve visited around the world, there are places where the pain seems to radiate out of the walls and floor with a cold intensity. The walls have seen so much suffering that they appear to have absorbed it. We were able to walk inside the cells and close the doors behind us to have a clear sense of what the people who lived in this place endured. The back of each metal door was covered in writing etched in the paint. The small courtyard outside the isolation cells is covered by a network of barbed wire laid out in a grid so that even when you step out of isolation into the sun, there’s a cruel barrier between you and the sky.

In a separate area of the prison women served their time away from men. The isolation cells for black women now contain museum exhibits. In front of each of the doorways to the cells, a large placard bears the photograph and a biographical sketch of one of the women who served time on this wing. Inside each cell a video monitor displays pieces of interviews done with the women featured on the placards, and beneath the video screens, artifacts of the women’s lives are on display. One woman says in her video that she had the most beautiful wedding dress imaginable, and she waited a very long time for her incarceration to end so that she could show it to her family. The bright yellow gown hangs in the cell beneath the video screen that plays her story.

I could tell you far more about this incredible museum and its moving tributes to its former inhabitants–particularly the poignant memorials to Ghandi and Mandela–but time and energy do not permit me to do so. If you have the opportunity to visit Johannesburg, you should not miss Constitution Hill. The museum reminds all of us that our active participation is required in order for democracy to adequately function, much less flourish, and the exhibits at Constitution Hill encourage their viewers to grapple with notions of justice, freedom, and democracy because such things should never be taken for granted.

Andy and I have had quite a few more adventures since our trip to Constitution Hill, but they will have to wait for another blog post. We’ve been so busy that we’ve hardly had time or energy to write! More to come as soon as I am able. I’ll leave you tonight with one last image from Constitution Hill. These are the doors to the Constitutional Court, home of South Africa’s Constitution and one of the country’s greatest symbols of democracy. The door is carved with the twenty-seven rights guaranteed by the nation’s constitution, and the rights are written in a variety of languages, including sign language. May we each take a page out of the South Africans’ book and reflect on the rights that we have and on the struggles of those who have been and are being denied human and civil rights.