Dana hugging a child at a workshop for Teatro em Comunidades. Eddie Williams appears on the left.

My name is Dana El-khatib. I’m currently a rising junior at the university of Michigan, studying Economics. Though born in Ann Arbor to a Palestinian family, I lived most of my life in Jordan. For that reason, I constantly find myself comparing how different cultures approach different practices.

The Prison Creative Arts Project (PCAP) at the University of Michigan aims to provide arts programming among other things to incarcerated individuals in Michigan prisons, and returning citizens. This is done through drama workshops, a literary art review and an annual art exhibition. This past winter semester, I was one of six alternating facilitators for drama workshops in the Federal Correctional Institute at Milan. When people ask me why I decided to join PCAP, I think of many reasons that I could blab on and on about. I think about how I cannot make a moral judgment about the people inside because I didn’t grow up in the conditions that many of them did. I think about our dysfunctional educational system, I think about systemic racism, etc. However, if I’m being honest, one of the biggest reasons I chose to do PCAP is for my own selfish desire to grow as a person. There is a word in Arabic that has a special value in Islam;الصبر; pronounced as“alsabir.” Though I do not believe there is a direct translation in English that could embody all of its meaning, if I had to explain it, I would say it’s a combination of resilience and patience. This concept has become more and more important for all Arabs due to the economic and social conditions the region faces. Even more than that, its value has become rooted in Palestinian culture with resistance and struggle. Although everyone faces adversity in their lives in many forms, I, having lived a very fortunate life, knew that I could learn a thing or two about alsabir from the incarcerated, and that’s why I initially joined PCAP. Imagine growing up in horrible economic conditions and then being stripped of your freedom because of the life that society has pushed you towards. Yet, I have never seen more forgiving and positive people than the individuals I have worked with on the inside. When setting guidelines for the workshop in Milan, two of the men immediately said that one guideline should be: peace and love at all times. If I had been in their shoes, I think I would have so much hate and anger in me that I would want to get revenge on this world, but most of the people I have met seemed to have a wonderful soul that just wanted to better their life; that is what I see as the embodiment of الصبر.

In Brazil, I wondered how the different social and cultural scene would affect how people reacted to their living situation. When we visited a facility specifically for mothers who give birth in prison and their children, I was amazed by the strength of the women. In Arab culture, when a woman gives birth, everyone is there to help her. The grandmother or mother-in-law also usually stay with the mother for a couple of months to help manage the burden of a newly born baby. As I watched the mothers in the prison holding their crying babies, I compared the life they live with the life that I had always expected a new mother to be living. There was no outside support or comfort. No one to hold you when you don’t know what to do, no one to take care of your crying baby at night so you could rest. You only had yourself and the other women in the prison. I tried holding as many crying babies as I could so that the women could have the closest possible experience to a normal workshop, but I knew that there is only so much of your reality that you can escape for a few minutes. I saw the women care for each other’s babies; I thought about their solidarity together. This doesn’t even compare to the burden of knowing that in a matter of six months, your baby will be stripped from your hands, and often put into foster care if the mother’s family does not take them in. Yet, I saw the women smile and laugh. One said she named her son Moses after the prophet, because she feels that he is a warrior in this prison; this gave her strength. Again, I thought about how resilient and patient these women were. I admired the amount of صبر they had and only hoped that I could be nearly as strong in my life.

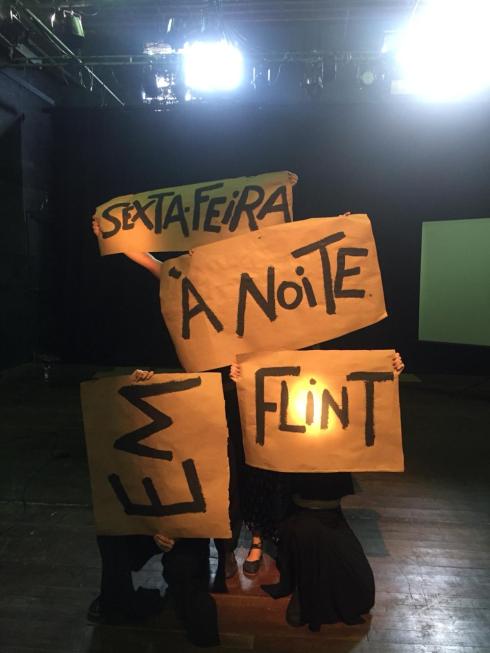

The favelas offered a whole new look into what this strength could mean to a community. We facilitated workshops for adults and children in what is known as a favela. A favela is a unique low income area in Brazil. Looking at the favelas and walking through them, I felt as though I had already been there. They were almost a carbon copy of the older and more established Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan. The children had the biggest and brightest smiles. The elderly had the strongest spirits even after living so long in such harsh conditions. On the bus ride back, a friend of mine was very sad. When I talked to him, he said he kept thinking about all the shit these kids have been through in their lives. I simply smiled and said, they have the strength to handle it. I really do believe that the universe does not throw something on you that you cannot handle. These children are raised in circumstances that enable them to develop a level of صبر that we can’t even understand or compare to. They find ways to carry on and strength that radiates through their smiles. I wish no one in the world was put in such conditions, but the truth is many are living these conditions and worse everyday. If we want to wallow in sadness of how depressing that is, we surely all can; but that won’t do anyone any good. I admire their strength and I do not fear that they will not survive because I know they will. I refuse to think of them with pity, but I insist on admiring all those who have lived through much worse than what I have experienced because the truth is, they can teach us a lot.